Chariot racing

Thrills, spills and crashes guaranteed at the ancient chariot races

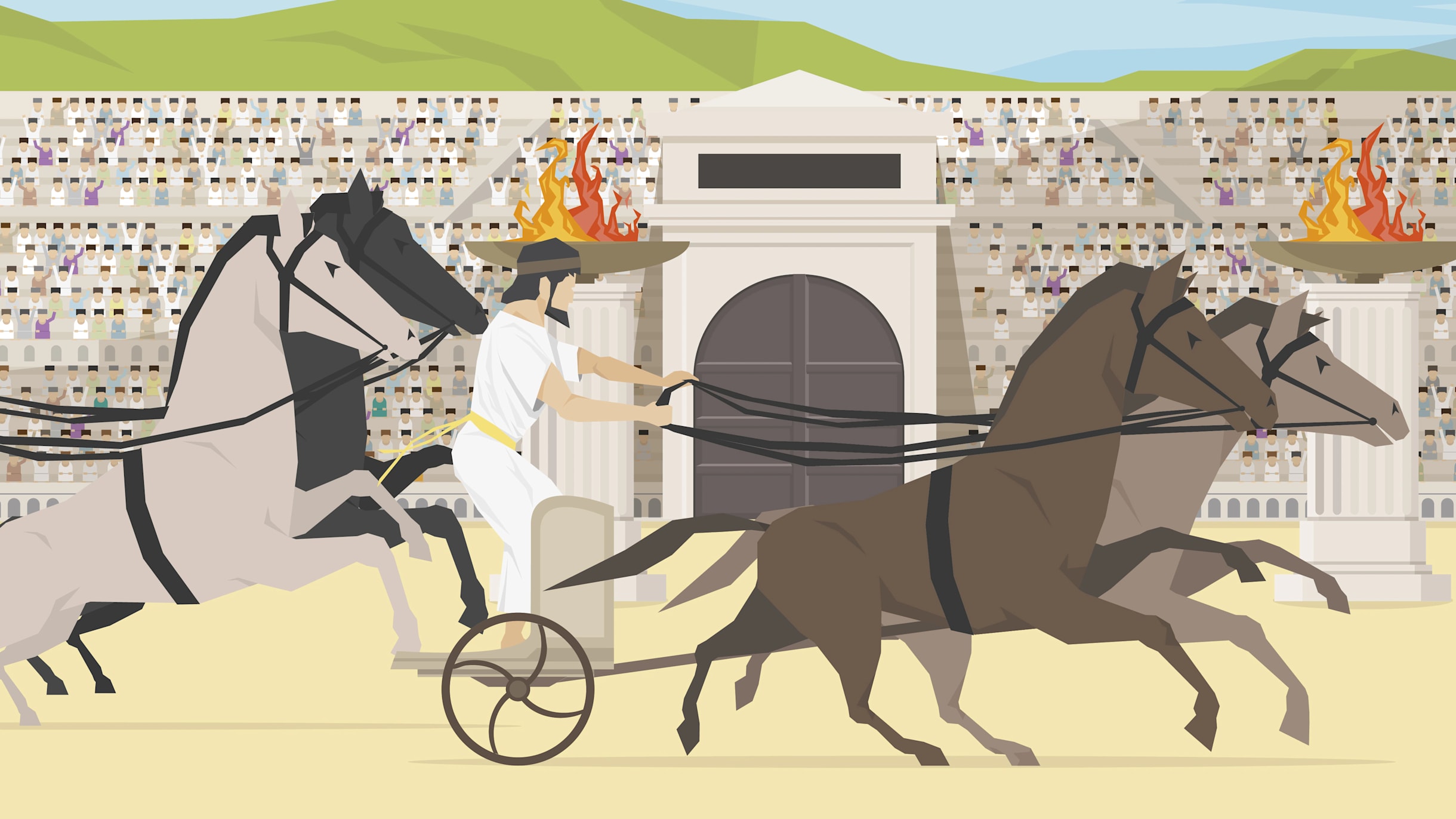

Chariot racing is one of the most thrilling, visceral and danger-filled sports ever invented by man. Present at the Ancient Olympic Games from 680BC, it continues to capture our attention and fuel our imagination more than two-and-a-half thousand years later.

“You can’t quite comprehend the power of four horses when they hit stride together,” said Boyd Exell, the four-time four-in-hand International Equestrian Federation (FEI) world champion – just about the closest thing we have to a modern day charioteer.

One horse is as strong as 10 men, when you multiply that by four you get that power and strength into one motion, the acceleration and g-force is unbelievable.

The four-horse chariot race was the most popular, prestigious and long-lasting event on the equestrian programme at the Ancient Games. With the driver perched on a wooden-wheeled, open-backed chariot, which rested on its own back axle, teams would funnel into an ingenious starting gate in Olympia’s specially-constructed Hippodrome. The mechanism was the shape of a ship’s prow, facing down the track. At the sound of a trumpet an imperious eagle would rise at the point of the prow as a dolphin fell, this movement would precipitate the rising of the ropes holding in the back markers at either side. As these chariots emerged and drew level with the ones in front the ropes holding them in fell and so on. Eventually, all the chariots would be level, hurtling down the track together.

There is a reason why the chariot-racing scene in the 1959 movie Ben Hur remains one of cinema’s most spectacular sequences of all-time.

“Even if you see one eventing horse gallop past you or a host of race horses it’s pretty impressive, so when a team of horses gallop past you it can be a little bit overpowering,” Exell said.

“When I am on the ground, I have to take a deep breath and remind myself I have done it before,” he added, a little nervously. Some of the Australian’s horses did in fact appear in the 2016 Hollywood remake of Ben Hur.

The battle to be first to the turning post was critical in chariot races. Similar to Formula One, the benefit of racing into fresh air and securing the inside line was almost incalculable. Collisions were inevitable. Locked axles, shunts and dropped whips could lead to staggering flips and smashes and, of course, life-threatening injuries.

Presented with the chance to race sulkies (two-wheeled modern carriages remarkably similar to ancient chariots) at the age of just eight – a misguided attempt by his mother to throw her son off his obsession with horses – Exell has some idea of the electric thrill and immense danger the charioteers would have faced.

“We (he and his 10-year-old brother) were irresponsible children with fast animals and sulkies,” the Australian explained. “We ended up in quicksand, going through rivers with water rushing over the horses’ backs, a lot of broken sulkies and broken harnesses.”

In the Hippodrome, riders were not allowed to veer from their course until they had open track in front of them. Controlling four powerful horses with a whip while cornering at full speed and attempting to evade a host of rivals out to get you was no mean feat.

The instinctive bond between driver and horses was clearly key, with the strongest, liveliest horse always placed on the outside to help the chariot corner. In his own, refined way, Exell knows just what the drivers were going through.

“The horses at the back of the carriage are called ‘the wheelers’ and it is quite good when they are worriers,” the 44-year-old said. “If the carriage is going to hit a tree or a post those horses will sense it and move away. The leaders at the front have to be bold and brave.”

The four-horse chariots raced 12 times around the track, covering about 14,000m. Rather unfairly, all the glory went to the winning owner, including the fabled olive wreath. This made the Hippodrome a fulcrum for wealth and power, with many of the ancient world’s most prominent figures owning chariots.

It was also an opportunity for women to be indirectly involved in the Olympic Games. Kyniska, daughter of the Spartan King Archidamos was one such female ‘Olympic champion’.

Kyniska of Sparta

At Olympia: Won the four-horse chariot race in 396BC and 392BC.

Back story: Daughter of the King of Sparta, Kyniska had her sights set on Olympic glory from an early age. Permitted by custom to win an Olympic wreath as the owner of a chariot, she evaded the rules banning women from competing.

Trend setter: Kyniska’s victories set the way for female owners, with a total of 12 claiming victory by the end of the Games.

While the drivers, like the horses, received just a woollen band tied around their heads in return for risking life and limb, a skilled charioteer did become highly sought after and well rewarded. Antikeris of Cyrene is said to have shown his driving skills to Plato by driving round and round the Hippodrome at full speed without ever leaving his own tyre marks. While Karrotos, charioteer for the King of Cyrene, is purported to have raced against 40 others, all of whom crashed, leaving him unscathed to collect his prize.

Within it all, it is refreshing to read that the horses themselves were not forgotten. Often raised with Olympic victory in mind, there is even an account of the horses of Kimon having their own tomb in Athens in recognition of a hat-trick of Olympic titles.

As the indefatigable Exell reflects on competing in the FEI Indoor World Cup Series in Stuttgart, you get a good idea of why this sport remains so intoxicating.

“You go up this ramp and you feel like a gladiator going into the thunderdrome,” he said, laughing.