Long jump, Javlin, Discus

Ancient field event techniques make “perfect sense”

From flute music to slingshot mechanics, the long jump, javelin and discus at the Ancient Olympic Games stand out for their intricacy and innovation. Gold medal-winning coach Toni Minichiello is impressed by what he hears. The long jump, javelin and discus are, of course, familiar Olympic disciplines, but their presentation at the Ancient Games varied significantly from that which is on show today – and not just because all the competitors were naked and covered in oil.

The long jump

The long jumpers hit the track at Olympia accompanied by the calming and peaceful, if slightly unlikely sound of flute music. No doubt in a zen-like state, the athletes would then stand at the top of a reduced runway holding a large stone or lead weight in each hand. Forward momentum was first achieved through a short, powerful run up, during which they swung the weights back and forth. At the take-off point competitors would thrust the weights back vigorously before stretching their arms back out in front of them to meet their feet. At the apex of the jump, arms would be flung backwards again, using the weights as counter-thrusts. Finally, just before they hit the earth, the athletes would discard the weights to ensure their hard-earned momentum was maintained.

It makes perfect sense. It is about generating horizontal force and then converting that force into lift. And those additional weights would give you more lift and carry more speed across the initial point of take-off.

The stones varied in weight from 1.4-2.0kg to suit the different sized athletes. With smooth grooves in them to help grip, the shapes also varied, from rectangular, to semi-circular and then hemispherical and elliptical.

While Minichiello is yet to utilise the weight method in training, he does see the value of any technique that can give an athlete the feel of jumping further.

“We long jump off a board,” he said. “We put a board or a platform at the point of take-off so you take off a little bit higher, therefore you get more lift off the floor, which gives you more time in the air, which means you can practise flight technique, landing positions, so on.”

The gentle music also hits home with the award-winning coach. “There are lots of studies done on the effect of music,” he said. “It is a distraction tool, a motivation tool. Certainly a lot of athletes use music (nowadays) when they are warming up, to get in the right frame of mind.”

It is not clear how far ancient Olympians jumped thanks to these helpful tools, given that the Greeks were solely interested in victory. However, there are two accounts of individuals leaping impossible distances, including the 664BC Olympic champion Chionis of Sparta clearing 52ft/15.8m. These, for a time, gave rise to the idea that the triple jump may have featured at some Games. However, most scholars have now decided this not to be true and the mythical distances to be down to understandable embellishment.

The javelin

Wooden, the height of a man and with one end pointed, the javelin was the most clearly militaristic event on the entire programme at the Ancient Games. While most did not have an iron or bronze point, the similarity to the spear, which almost every competitor would have handled during his life, is clear.

The key difference to the modern javelin was the use of a leather strap which the athletes would loop around the javelin’s centre of gravity. Latching two fingers into the loop, competitors would send the javelin skyward using much the same, side-on technique as employed by today’s Olympians.

“It is a slingshot really. It makes perfect sense,” Minichiello said. “We use heavy and light javelins (in training) for the same reason. If you can throw a lighter implement it speeds up your movement pattern and heavy implements develop a bit more specific strength.”

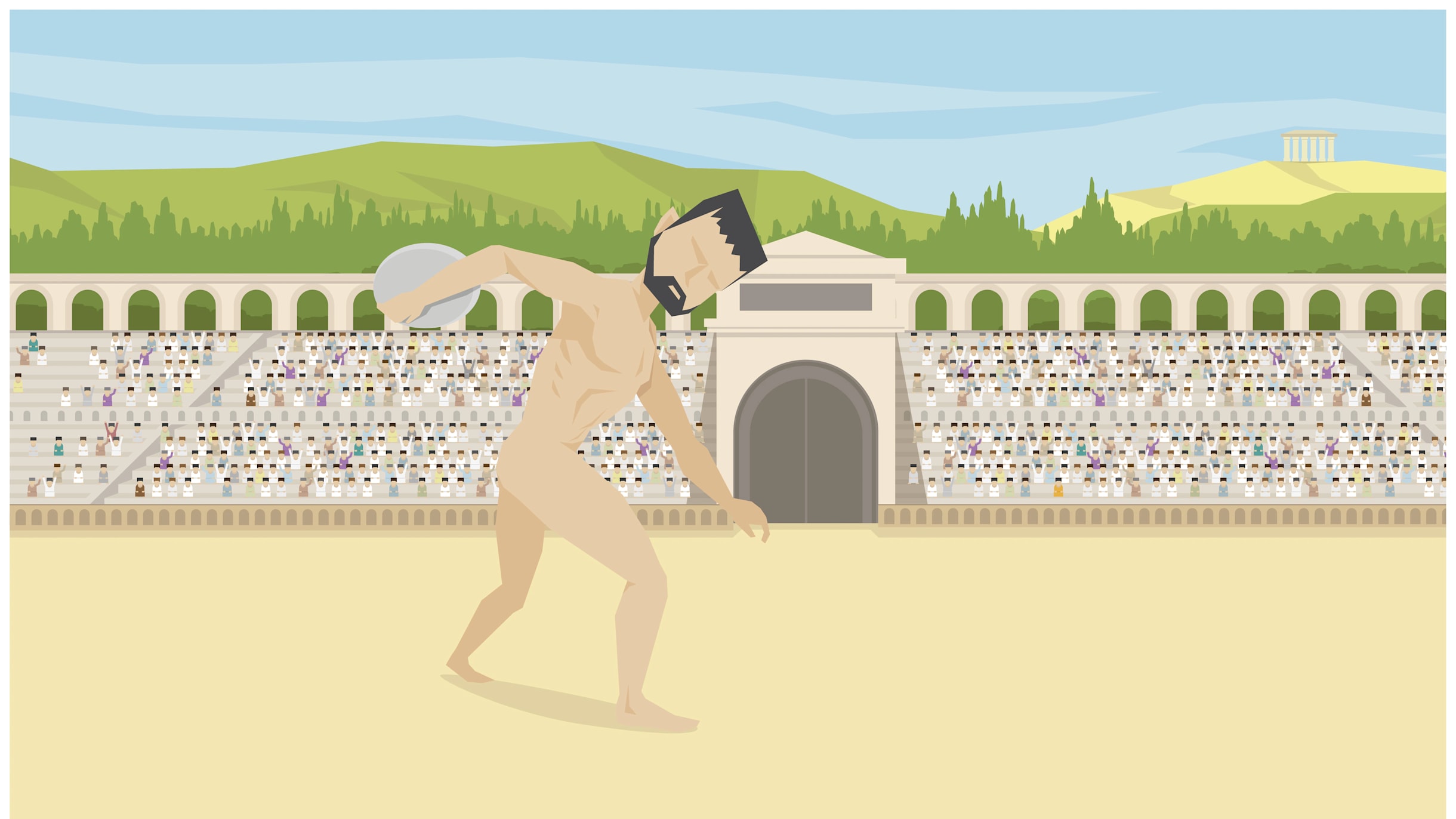

The discus

Like the javelin and the long jump, the discus was part of the pentathlon, but, as the only discipline on the entire Olympic programme not to have any obvious link to everyday life or warfare, it is a slight anomaly.

Despite this, the discus has a long tradition in the Greek world, first mentioned by Homer. Strangely, it also has a close connection with death in Greek mythology. Both Apollo and Perseus accidentally killed loved ones with errant throws.

Often engraved with picturesque scenes or poetry, discuses were made first of stone and later of iron, lead or even bronze. It seems that the set weight of the discus varied from Games to Games, with discoveries ranging from weights of 1.3-6.6kg and diameters of 17-32cm. Launched in a similar manner to that employed by modern athletes, there is a record of Phayllos of Kroton throwing 95ft/28.9m.

All three of these field sports required rhythm, precision and power, qualities highly valued by the Ancient Greeks.