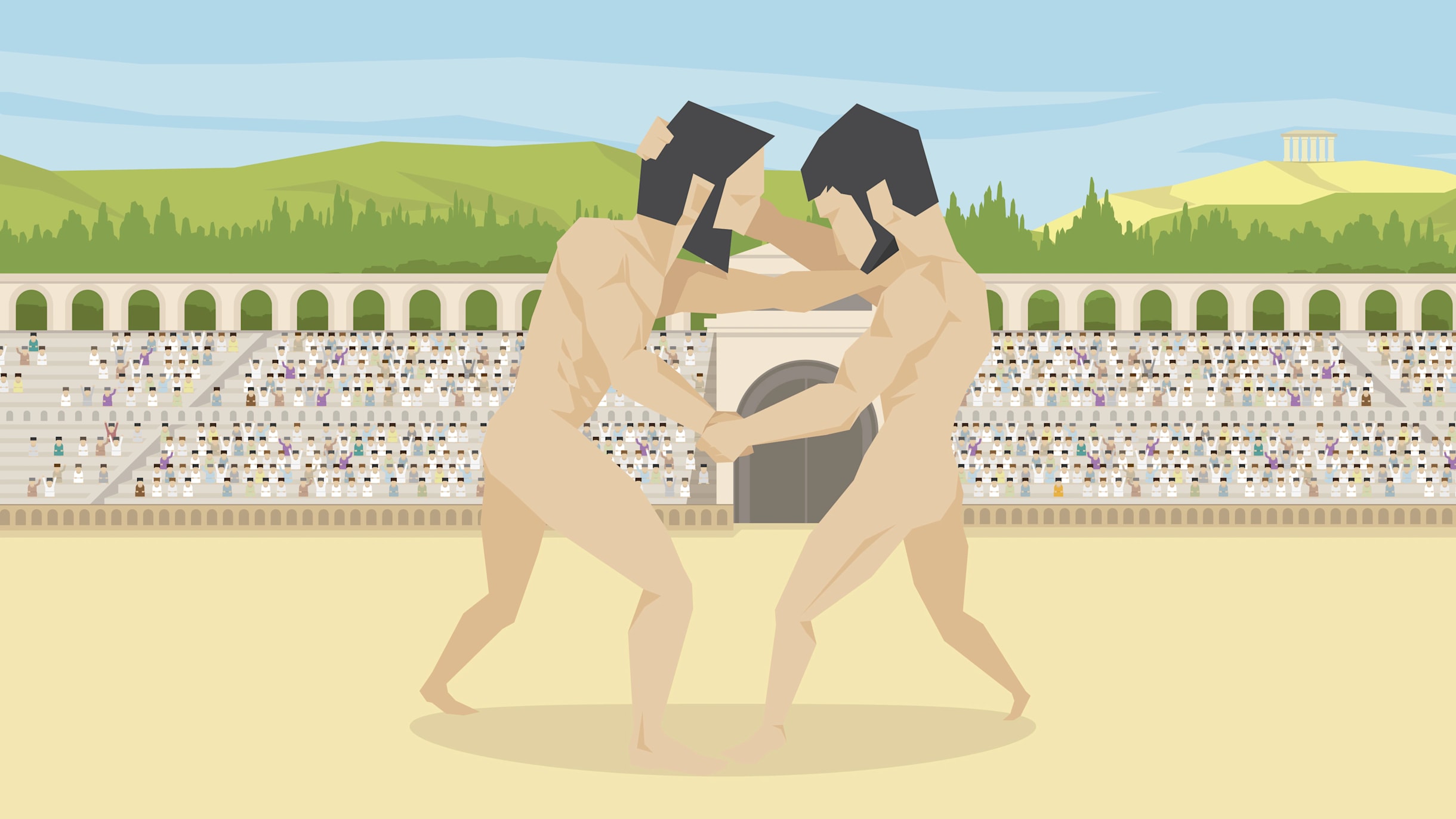

Pankration

‘No biting and no gouging’ - but all else fair game in “brutal” pankration

A combination of boxing and wrestling with barely any restrictions, pankration was the wild, no-holds barred centre of the Ancient Olympic Games. Boasting huge men of incredible strength, it became a fountain of wondrous stories and stirring myths.

Pankration was a magnificently simple sport.

“You could do pretty much anything you could possibly imagine in order to incapacitate your opponent,” Paul Christesen, Professor of Ancient Greek History at Dartmouth College, USA, explained. “And the Greeks thought this was the coolest thing ever.”

As with all sports, the Greeks believed a god or a hero to be responsible for inventing the rules, and in the case of pankration it was down to Theseus. The mythical man came up with a combination of wrestling and boxing to defeat the Minotaur, the half-man half-bull said to have lived in a labyrinth below the palace of King Minos of Crete.

No biting and no gouging were just about the only restrictions in Theseus’ sport, although, the ever hard-core Spartans allowed both in training in order to ready their warriors for war. Unlike boxing, hands were left bare in pankration. Typically tall men favoured punching as their go-to-tool while a stocky competitor was more likely to wrestle. Both types sought the key move, a stranglehold with one arm, leaving the other free to repeatedly punch the unfortunate opponent.

The first to fall was in trouble, liable as he was to being disabled by his adversary who would then be free to implement the feared stranglehold. There are, however, accounts of smaller, more agile fighters tricking their rival by seeming to fall to the ground in distress in order to lure their cumbersome opponents into a position whereby they could use their legs and arms to destabilise them before leaping off the floor and administering a bout-winning blow.

We know that some people died. Our guess is that there were a lot of really nasty injuries but probably not a lot of deaths because either you passed out or you surrendered before you died. For example, if someone broke all the fingers in your right hand, which was a perfectly reasonable thing to do in pankration, at that point you probably said, ‘Listen, I think that is probably enough for me’.

The tale of Arrichion of Phigaleia neatly expresses why, for the Greeks, this was one of the most hotly anticipated events on the Ancient Olympic programme. Caught in a terrible stranglehold, Arrichion seized the foot of his opponent and, with the last of his strength, crushed it, dislocating the ankle. Unable to bear the pain, the unnamed man raised his index finger to signal submission. At the very same moment Arrichion gasped his last breath. He was posthumously awarded the victory because his rival had surrendered.

“The Greeks were willing to tolerate a much higher level of violence in sports than we are for the most part,” Christesen explained. “This goes back in part to the issue that people who were athletes tended to be soldiers and vice-versa. So there was, in some sense, a habituation to violence. You were expected to be ready to do that sort of thing on the battlefield, so there was less squeamishness about doing it during sports.”

Seven athletes won the heavy combat double of wrestling and pankration at the same Games, including the unfortunate Arrichion. But Theagenes of Thasos is the ultimate symbol of this brutal and wildly popular sport.

Born to a priest in the temple of Herakles on the island of Thasos, the locals came to believe Theagenes’ true father was the god Herakles himself. Famous from the moment he tore a bronze statue from its base in the square in Thasos and carried it home aged just nine, Theagenes went on to win the boxing at the 75th Olympiad (480BC) and the pankration at the 76th. Subsequently, he toured the Mediterranean basin reportedly winning more than 1400 victory wreaths. A life-size statue of the man stood in Olympia itself.

The nature of the sport naturally encouraged legends to grow up around its fearless heroes. None more so than for Polydamas of Skotoussa. The Olympic champion in 408BC is said to have killed lions with his bare hands, pulled the hoof off a ferocious and furious bull and brought a speeding chariot to a standstill with just one hand.

As an amused Christesen points out, there was one other hugely beneficial outcome to this obsession with heroic deeds and brutal one-to-one combat.

“The Greeks invented sports medicine, probably in part because of all the injuries all the time,” he said. “They became experts in trying to solve injuries incurred during sport.”