"Free Speech for Olympic Athletes"

11 Feb 2020, by

Richard W. Pound

IOC Honorary Member

Olympian

By Richard W. Pound, IOC member & IOC doyen

When critics apply their denouncements with a palette knife or fling them on canvas like Jackson Pollock, intellectual rigour is often lost in the swirl and splash. Similarly, when the operational matrix is “ready – fire – aim”, insufficient attention gets paid to context. In the compulsion to shoot, accuracy is sacrificed.

Take the International Olympic Committee (IOC)’s Rule 50 for example. It provides that no kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas. A subset of this rule applies to medal presentations and prohibits demonstrations on the podium. There is a perfectly simple explanation for such a rule, but in some quarters it has been harshly criticised as an unjustifiable incursion into the rights of free speech enjoyed by Olympic athletes.

Let’s set a few facts in order.

Now, back to Rule 50 and the misguided furore surrounding it.

First, this is not a new rule and, second, it is one wholly consistent with the underlying context of the Olympic Games, during which politics, religion, race and sexual orientation are set aside. The guidelines causing the furore were produced by athletes themselves, after extensive consultations. It is athletes who bear the risk of losing the moment they have trained for their whole lives by a protest on the podium.

Everyone has the right to political opinion and the freedom to express such opinions. The IOC fully agrees with that principle and has made it absolutely clear that athletes remain free to express their opinions in press conferences, in media interviews and on social media. But, in a free society, rights may come with certain limitations. Rule 50 restricts the occasions and places for the exercise of such rights. It does not impinge on the rights themselves. Many other governmental and sporting organisations have similar rules restricting demonstrations. Remember, too, that allowing protests on the podium means accepting all protests, not just those with which you may agree.

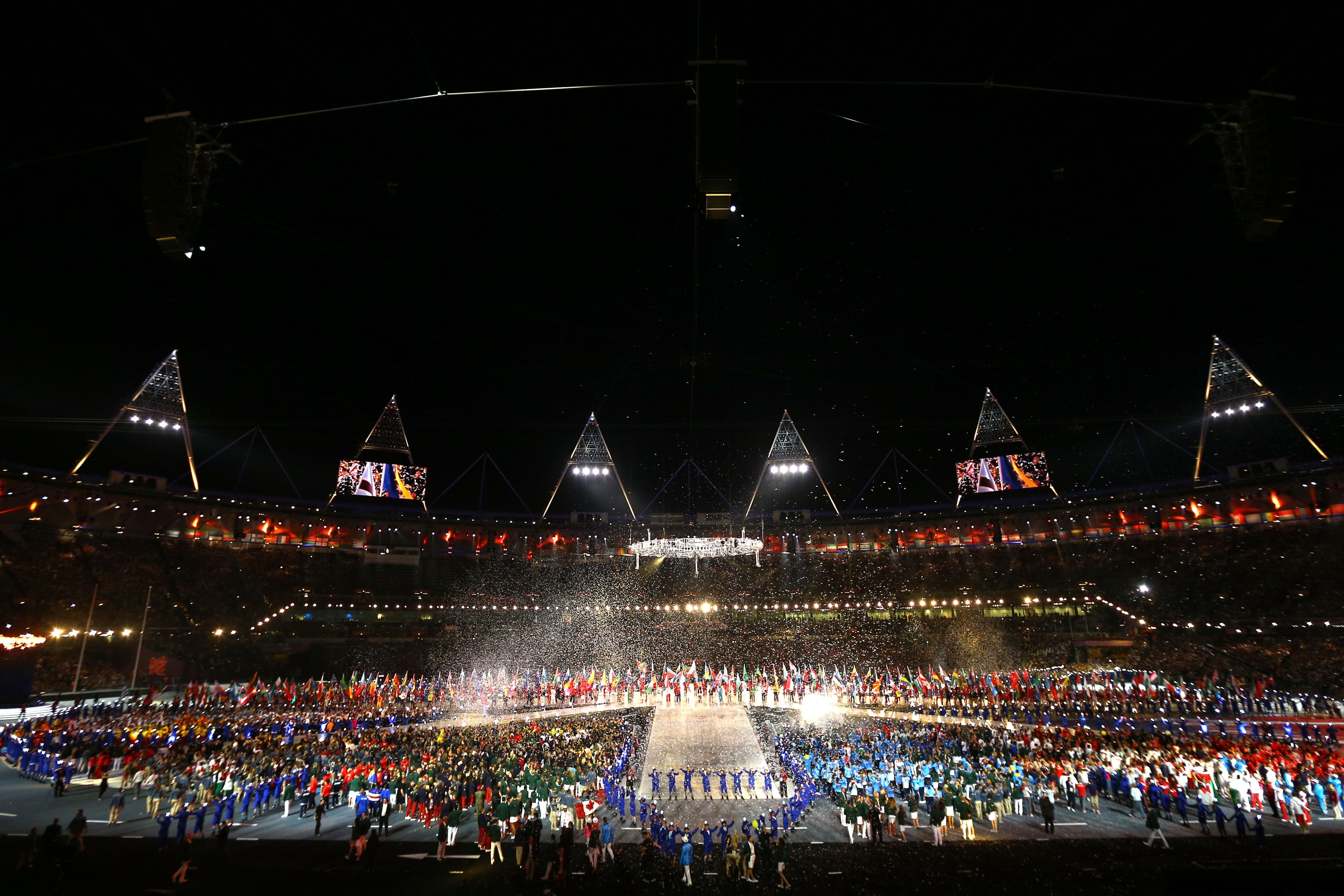

As is the case with countries, no organisation is perfect. Some, however, including the IOC, are committed to principles and aspirational goals. The IOC is committed to using sport to bring people together in peaceful circumstances, to using it as part of their overall development and to helping expose them to others from around the world. The Games can demonstrate to the world that all things are, indeed, possible, if there is a will to make them happen, tempered by goodwill and mutual respect.

Rule 50 is a reminder that, at the Olympic Games, restraint is an element of that mutual respect. It is entirely appropriate for the IOC, which created the Games, to establish rules that are consistent with the fundamental underlying principles. It is not hubris, as some critics have claimed, but rather a conviction that a better world is possible with a balance of rights and concomitant responsibilities.

It is our lot to be living in a highly differentiated world. It is our duty to bring about change, to create consensus on living together in a manner that respects, not condemns, diversity, and that accepts the right to be different, understanding that there is no perfect ideology or a one-size-fits-all paradigm. The human equation is too broad for such an ersatz solution.

The Olympic Games are, in themselves, no panacea for all of the challenges that face us. But the principles that give rise to the Games can illuminate a way forward that integrates fundamental humanistic values. Avoiding vengeance, especially misguided vengeance, is an admirable beginning.

Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter codifies that important principle. We all need to be reminded of what we have inherited and, without sacrificing any right to freedom of speech, embrace the special experience of the Olympic Games as a building block for a better future.

Richard W. Pound is an Olympic finalist in swimming for Team Canada at the Olympic Games Rome 1960 and a lawyer by profession. First President of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) from 1999 to 2007, Pound is the IOC's longest-serving member, having joined the organisation in 1978.