The Olympic pictograms, a long and fascinating story

Markus Osterwalder is the Secretary General of the International Society of Olympic Historians, specialising in the graphic and general design of each edition of the Games. Here, we take a look with him at the history of sports pictograms which, he tells us, did not begin in Tokyo in 1964, but a lot earlier than that!

“I started to take an interest in Olympic graphic design, of which pictograms are a part, in the early 1990s, when I began studying at a Swiss graphic arts school,” Osterwalder explains. “I had to prepare my final thesis, and I decided to take a look at Olympic design. I went to the Olympic library in Lausanne, and on the day I arrived I saw the book on the design of the 1994 Games in Lillehammer. That inspired me and totally changed my life, in the sense that it told a fantastic story about what graphic design can be. Not only from a functional point of view, but far more because it is a part of a country’s heritage, representing a nation, a vision, a philosophy. After that, I really started to investigate, and undertake a lot of research, which I have continued right up to now.”

It is generally agreed that Olympic Games pictograms were really first introduced in 1964, in Tokyo. But Osterwalder explains: “Creating symbols which are not letters but graphic illustrations that everyone can understand goes back much further than that. I’ve found small pictograms that were at the Games in Stockholm in 1912, Paris in 1924, and other Games after that; but they did not yet offer that very simple and clear view that we know today. They were complicated illustrations, but not verbal elements, describing sports, art competitions or other things. For example, for the art competitions in Paris in 1924, there was a symbol, an illustration, which may be considered a pictogram.”

However, the team of designers who worked on the Summer Games in Tokyo in 1964 did a lot to shape the system what we know today. “They reduced the shapes and sizes to the minimum needed to understand the message. The Japanese were faced with the problem of language. Nobody speaks Japanese outside Japan. So they really had to find something that would work for all the people from other countries. A non-verbal system.”

“Take the emblem of these Games, for example [a red disc above the Olympic rings and the words Tokyo 1964]. It is so simple, if you tried to remove any part of it, it would no longer work. They invented a very simple new language, and a totally new form of graphic design. They used sports photography for the first time, and typographic unity as a graphic element. That had never happened before. Tokyo 1964 had brilliant designers, who knew what they wanted to do and did some fantastic work. It was Tokyo 1964, for example, that invented the pictogram for men’s and women’s toilets.”

An important turning point at Lillehammer in 1994

Osterwalder observes that there were no major changes after that in the 1960s, 1970s or 1980s. “They all looked similar. There were some differences in style, with some being more comprehensible than others, but it was the same philosophy.”

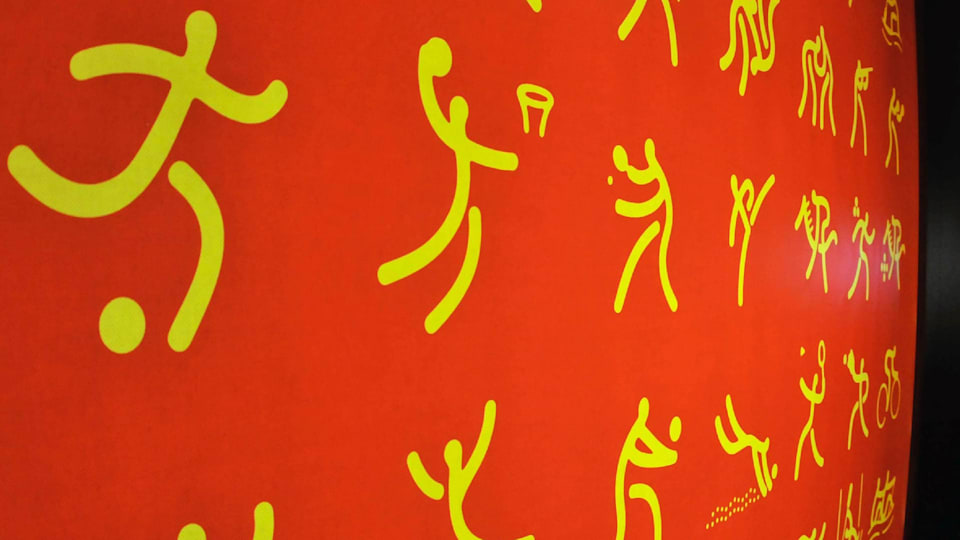

The most important evolution came in the 1990s. Albertville and Barcelona for the Winter and Summer Games in 1992 devised their own pictograms using the brush painting technique. And these then became an integral part of the general design, like the Cobi character, which had versions for all the sports.

“A new and important change took place for the 1994 Games in Lillehammer where, for the first time, the pictograms told a story. They were based on the famous 4,000-year-old rock carving found in a cave [representing a man on skis]. For the first time, a country’s heritage was incorporated into the graphic design, something which belonged to Norway and was linked to the winter, or winter sports. It was there that pictograms began to tell a story,” he explains.

“In Sydney in 2000, too, all the pictograms were based on the boomerang, with totally new figures to represent the sports. For Athens 2004, they also used their heritage, by recalling the ancient Games with modern graphic design. Pictograms which really reflected the country’s heritage. Today this has become the normal thing to do. In some cases, this fits in perfectly with the overall design of the Games; but in others, it looks a bit odd. In Turin in 2006 and Vancouver in 2010, they used a three-dimensional design, with different layers. Those for Sochi 2014 were based on the pictograms for the 1980 Games in Moscow. In Rio in 2016, they fitted perfectly with the general Look of the Games, but had no real story to tell.”

For the Swiss Olympic design historian, “the first use of pictograms was to give people a message, without their having to read anything. To go to the Olympic Park or the various venues, and say, ah right, there’s the press room, there’s such-and-such a venue, etc. All these pictograms for signage and the sports are the Games guides. Without them, just imagine how many languages you would need to use for everyone to understand. Pictograms make things much simpler!”

Of course: “It’s even better if they also give you a clue as to the flavour of the Games, their heritage, their look, and so on; and if you can use them for merchandising as well. In Lillehammer, for example, they produced thousands of T-shirts and objects featuring the pictograms, and people loved them. If the pictograms are no good, you won’t sell anything! In such cases, they are perhaps symbols which allow people to understand that the sport is basketball or sailing, but nothing more than that. Moreover, those from the 1960s to the 1980s were purely informative, nothing more. And then that changed. They became part of the heritage, the Look of the Games and the commercial programme.”