Paris 1924 Olympic Games and Pierre de Coubertin’s enduring love for France

The Games of the VIII Olympiad embodied Pierre de Coubertin’s vision for the world’s greatest sporting spectacle, with many of his ideas remaining relevant today.

By George Hirthler

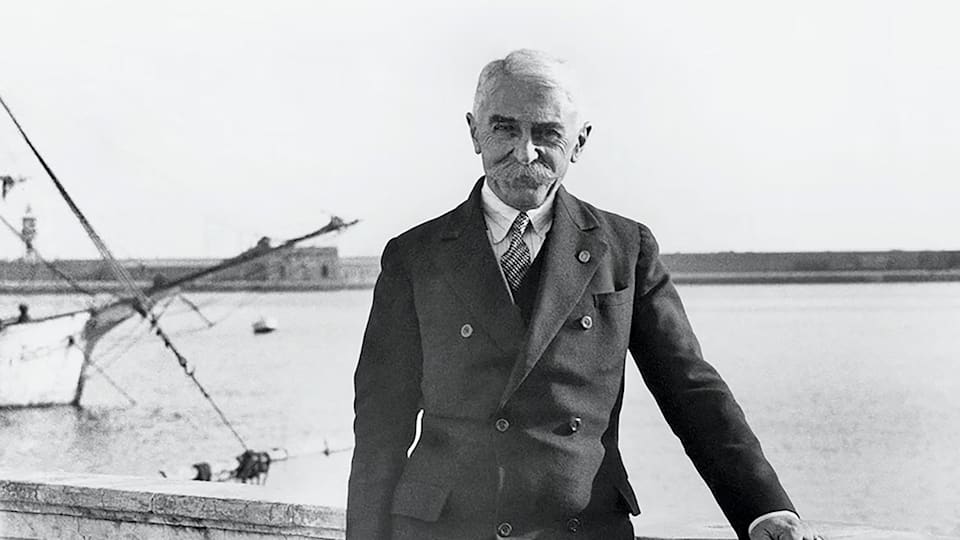

The Olympic Games Paris 1924 were Pierre de Coubertin’s swansong. As a master of theatrical impact, he had prepared the stage for his exit years before. When he had announced his retirement in 1921 – in a poignant letter sent to his IOC colleagues – he asked them to grant him one last wish “… in favour of (my) native city, Paris …” and award the 1924 Olympics to his birthplace while naming Amsterdam host of the 1928 Games. He knew the IOC would not deny him the privilege of celebrating the culmination of his historic Olympic work in the capital of the country for which he first proclaimed his “wild passion” at the age of 12.

As much as he loved the Olympic Movement, which he had launched at the Sorbonne 30 years before, Coubertin loved France even more. He wrote continuously of its history, sought to promote its stature internationally, embedded its language and values at the heart of the Olympic Movement, and admired above all the success of the Third Republic, to which he had rallied in his twenties to lend his considerable intellect and talents to the challenges of French education reform in the 1880s.

In fact, his original motivation for resurrecting the modern Olympic Games was anchored in his hopes that the event itself might deliver glory to his home country. In 1909, reflecting on Germany’s excavation of ancient Olympia from 1874 to 1880 during his teenage years, he wrote: “Nothing in ancient history had given me more food for thought than Olympia. This dream city ... loomed with its colonnades and porticos unceasingly before my adolescent mind. Germany had brought to light what remained of Olympia; why should France not succeed in rebuilding it splendours?”

As if to punctuate his love for France later in life, at the age of 52 in 1915, after moving the headquarters of the IOC from Paris to the safe shores of neutral Lausanne, Switzerland, he set aside his presidential Olympic duties to put on the uniform of the French army in defence of his nation in World War I. Too old to report to the front lines, he worked for the Ministry of War in the Propaganda Department, travelling around the French provinces giving lectures to stimulate the nation’s esprit de corps. Although he had launched a movement to foster peace among nations, when it came to France, Coubertin could not be a pacifist.

Returning to Paris in June of 1924 to put the crowning touch on his Olympic career, his heart brimmed with emotion and his mind was crowded with thoughts of what he had achieved and what he was about to leave behind. With the pride of a patriot, he believed that Paris – the indisputable cultural capital of the world – would put the final seal of immortality on his life’s work and ensure that his global movement for friendship and peace through sport would have a permanent place on the international calendar. Having once again resurrected the Games after the devastation of World War I, in Antwerp in 1920, a Games which by necessity had a military bearing, he was counting on Paris to lift the celebration to heights of athleticism and culture that would exceed by far the previous six Olympiads and finally fulfil his extraordinary vision.

All the signs suggested he would not be disappointed. The Opening Ceremony was scheduled for 5 July, and teams from 45 nations were already settling into the new Olympic Village – a French innovation that symbolised the worldwide unity the Games sought to foster. A record number of 3,089 athletes, including 135 women, were set to compete.

But before the feats of athleticism began, the 30th anniversary of the founding of the modern Olympic Games had to be properly enshrined in their birthplace. Amid a large crowd in the Court of Honour at the Sorbonne, Coubertin and his IOC colleagues welcomed the 13th and first Protestant President of the Third Republic, Gaston Doumergue, who had only been in office for 10 days. Out of gratitude for the host city and country, Coubertin presented Doumergue with a small case containing two gold medals, the first inscribed 30 years earlier as “The International Congress in Paris proclaims the revival of the Olympic Games, 23 June 1894”. The second commemorated the moment: “The nations assembled here to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the revival of Olympism, 23 June 1924.”

That night, President Doumergue hosted a banquet at the Élysée Palace for Coubertin and the IOC, offering toasts and official admiration for the Olympic Movement. A few days later, at another reception hosted at the Hôtel de Ville by the president of the city council and the prefect of the Seine, Coubertin let his gratitude flow, thanking Paris for lifting the Olympic Games toward new heights while reminding his hosts that whatever happened in the days ahead, his great global work would continue: “… the ocean of sport seems to have its ups and downs just like the salt ocean,” he said, but “… sport has become international and we may therefore hope that this movement will not stop, since if it were to weaken at one point it would revive at another.”

And then he closed his speech with a loud proclamation, “Long live Paris!”

Once the Games began, the quality of the competition sparkled with excellence. Johnny Weissmuller, the American swimmer who would go on to Hollywood fame as Tarzan, set an Olympic record in the 100-metre swim, beating the previously unbeatable Duke Kahanamoku from Hawaii, who had won gold back-to-back in the previous two Olympics. The Paris Games showcased the running brilliance of Paavo Nurmi, who would go on to win nine gold medals in his Olympic career, and the Chariots of Fire heroes Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams. Despite his stated opposition to women competing in the Games, Baron de Coubertin never blocked their participation and the number of women competing grew sixfold under his presidency – and Paris served as the new pinnacle of that growth. As if to celebrate, the baron took his nephew, Christian de Navacelle, and his niece, Marie-Marcelle de Coubertin, to the women’s tennis tournament, where the 18-year-old American sensation, Helen Wills, who would ultimately win eight Wimbledon titles and become America’s first female global sports celebrity, beat the French champion, Julie Vlasto, for the gold.

While Coubertin had many battles behind the scenes with French sports officials in the lead-up to the Games, there is no doubt Paris 1924 delivered for le Rénovateur, marking the end of his era in the city of his birth by producing the finest Olympic festival yet staged. A year later, at the IOC Congress in Prague, Czechoslovakia, the baron would mount the podium in the town hall and challenge his colleagues to carry on his work as he stepped down.

In that farewell, Coubertin was full of gratitude, but offered his colleagues a series of warnings against the dangers ahead. Foremost among the principles he exhorted them to protect was universalism: “Is there any need to recall that the Games are not the property of any country or of any particular race, and that they cannot be monopolised by any group whatsoever? They are global. All people must be allowed in, without debate, just as all sports must be treated on equal footing, without concern for the fluctuations or caprices of public opinion.”

Even today, his message carries a moral immediacy that reflects the timeless qualities of his Olympic vision, which Paris and France were, and are, uniquely equipped to celebrate.

George Hirthler is an American writer. He is the author of the historical fiction, The Idealist, a novel about the life and times of Baron Pierre de Coubertin. He was awarded the Pierre de Coubertin Medal in 2022.

This article is an edited version of a third-party contribution that first appeared in the Olympic Review. The articles published in the Olympic Review do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the International Olympic Committee.