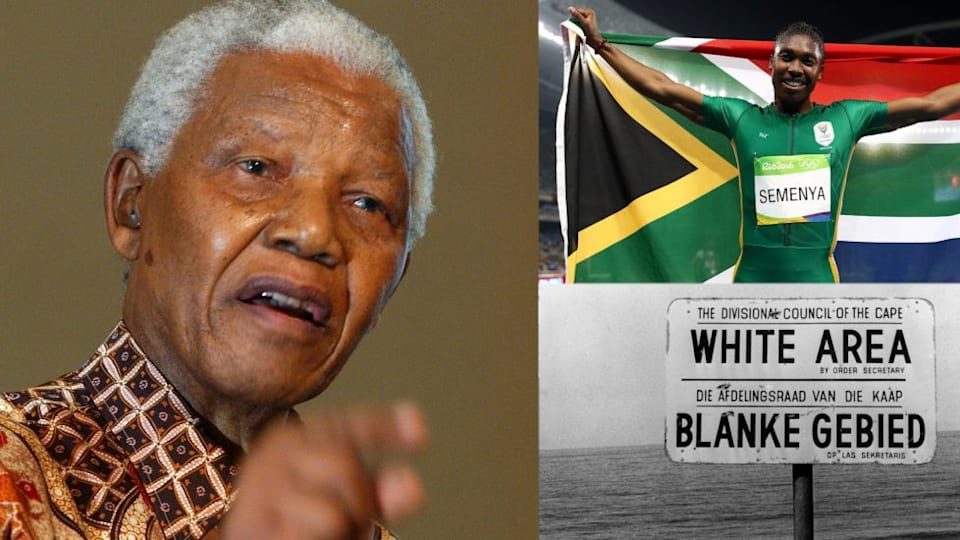

Find Out Why South Africa Was Barred From the Olympics for 32 Years

A generation of athletes were ineligible to compete due to Apartheid

While still a British colony, South Africa became the first African nation to appear at the Olympics in the St Louis Games of 1904.

South Africa appeared at every Summer Games until Rome 1960, winning 51 medals in the process.

But before the 1964 Tokyo Games, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided to bar South Africa due to its racial segregation policy known as Apartheid.

This saw non-white South Africans widely discriminated against in all aspects of life, including sport where only white athletes could represent the country.

Due to the persistence of Apartheid and the influence of other African nations, the South African Olympic Committee was officially expelled from the IOC in 1970.

It would remain an Olympic outsider for the next two decades.

Life under Apartheid

Apartheid was the South African government’s programme of racial discrimination and segregation.

While segregationist policies had existed since the early 20th century, Apartheid took full effect when the National Party won power in 1948.

Under Apartheid, restrictions were placed upon where non-white South Africans lived, worked and went to school.

Whites, Blacks, ‘Coloureds’ (primarily those of mixed race), and ‘Indians’ had separate neighbourhoods, public areas, buses, restrooms and hospitals.

Non-whites had to carry government-issued ID, or ‘passes’ at all times and needed permission to enter ‘white areas’. They were also not allowed to vote, protest, own property or run for public office

In 1959, new legislation divided the black South Africans into eight ethnic groups and resettled them outside of major cities.

Between 1960 and 1983, 3.5 million non-white South Africans were forced to leave their homes and move into segregated townships.

These townships were often in isolated rural areas with few jobs and widespread poverty.

After being relocated to townships, they were stripped of their South African citizenship.

Protesting Apartheid

In spite of restrictive conditions, a resistance movement was growing.

The African National Congress (ANC) led strikes and protests, including the Defiance Campaign of 1952 where black South Africans began entering white areas, buses and bathrooms and stopped carrying passes.

Eight thousand were arrested, but the movement failed to gain international attention.

In 1960, members of the Pan-African Congress – an offshoot of the ANC – protested the government’s ‘pass’ laws and restrictions on non-white movement.

An unarmed group protested peacefully in March but police responded with gunfire, killing 69 people and injuring 180 in what became known as the Sharpeville massacre.

That led to the government declaring a state of emergency and outlawing all black resistance parties.

Resistance leaders were soon convince that non-violence was no longer a viable option for fighting apartheid.

Long-time ANC leader and anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela helped found the party’s military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”). He later stated:

“It would be wrong and unrealistic for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the government met our peaceful demands with force. It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle.”

In 1962, Mandela was arrested and imprisoned by the South African government.

The same year, the United Nations passed a resolution condemning Apartheid and the IOC barred South Africa from the 1964 Games.

Mandela received a life sentence, but he remained the symbol of the anti-Apartheid movement.

While in jail, he studied law via correspondence with the University of London, smuggled out political statements, and drafted his autobiography, ‘Long Walk to Freedom’.

The situation in South Africa worsened further with Blacks angry at being taught Afrikaans, the language of their oppressors, in schools.

Between 10,000 and 20,000 students marched in protest in Soweto in June 1976, and the result was more bloodshed.

The Soweto uprising led to further international isolation and, despite an ease in restrictions towards Indians and Coloureds, Blacks were still being persecuted.

In the mid-1980s, the black townships saw a huge escalation in anti-apartheid activism.

President PW Botha declared a nationwide state of emergency in 1986 to crush dissent and protest as well as censor the press.

But mounting pressure from overseas and a fear of a full-blown civil war eventually led to Apartheid’s collapse.

FW de Klerk succeeded Botha in 1989 and allowed previously illegal marches and protests to go ahead as well as approving the release of political prisoners.

Early the following year, he lifted the 30-year ban of the ANC and on February 11, 1990, Mandela was freed from jail after 27 years.

He immediately became involved in negotiations to end white minority rule and the government started to repeal apartheid law in 1991.

Two years later, Mandela and de Klerk received the Nobel Peace Prize.

In April 1994, Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black president.

During his term, he established social and economic initiatives improving the standard of living for South African blacks.

He also oversaw the enactment of a new constitution, which prohibited discrimination against minorities.

A New Legacy

South Africa rejoined the Olympic movement in time for Barcelona 1992 with its first racially mixed national team.

And the Springboks rugby jersey, for so long a source of hatred for non-white South Africans, was embraced by the whole country when Francois Pienaar led the team to victory at the 1995 Rugby World Cup on home soil.

In the Olympics, South Africa has excelled in athletics and swimming.

Four-time Olympian Roland Schoeman medalled in the 50 and 100m freestyle and helped break world and Olympic records for the 4x100m freestyle relay at Athens 2004.

Hestri Cloete earned back-to-back Olympic silver medals in high jump, plus two world titles.

Nine-time national champion Mbulaeni Mulaudzi served as flagbearer in Athens, where he claimed silver in the men’s 800 metres.

Then came four individual gold medal heroes.

Caster Semenya has captured three world titles and two Olympic gold medals in the 800 metres.

After winning five medals in the first edition of the Youth Olympic Games in 2010, Chad le Clos won a gold and three silvers at London 2012 and Rio 2016.

Cameron van den Burgh also struck gold at London 2012 before taking silver in Rio.

And then there’s Wayde van Nierkerk who shattered the 400m world record to secure glory on his Olympic debut in Rio.

Van Niekerk’s mother was also a runner, but Apartheid stopped her competing in the Games.

You can hear her story in the third episode of the Olympic Channel original series ‘Foul Play’, premiering on July 18.