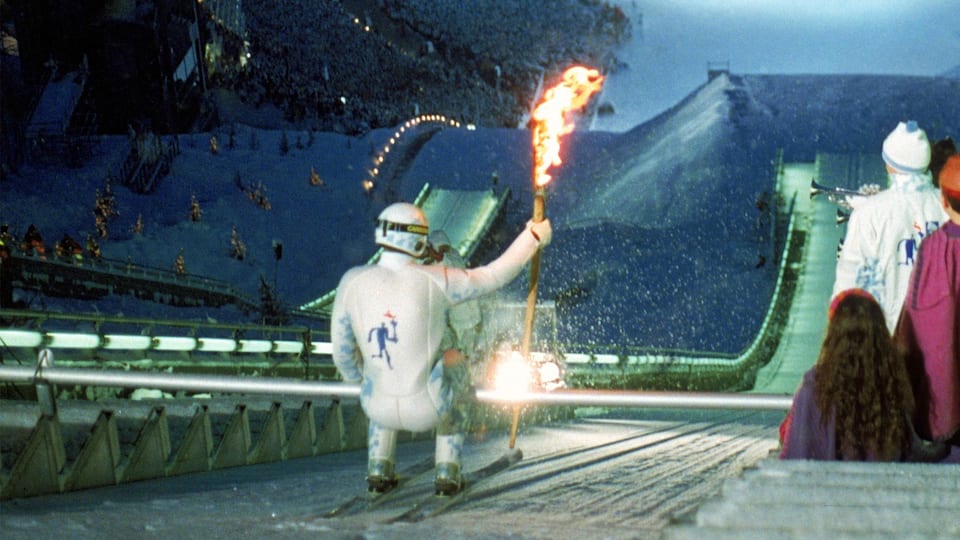

Snapped: the moment the Olympic flame prepared for take-off

Unbeknown to many, organisers of the Opening Ceremony for the 1994 Winter Games had long been preparing to launch the Olympic flame into the Lillehammer night sky. Inexperienced snapper Bob Martin was as in the dark as everyone else but, through a mixture of luck, ingenuity and talent, the Englishman soon found himself in the perfect spot to capture one of the enduring Olympic images.

Young sports photographer Bob Martin was furious at being sent to the top of the ski jump hours before the start of the Lillehammer 1994 Olympic Winter Games Opening Ceremony. Freezing cold, the keen Englishman was convinced he was missing out on a chance to prove his worth amid all the action below.

“Initially, I was fed up,” Martin laughed. “I thought I would only get one picture up there and those days I wanted to get a picture of everything. I was still quite young and all I was trying to do was take 100 pictures every day. I thought quantity was what it was about.”

Martin’s bosses, like many, were aware that a ski jumper would perform during the Ceremony and were hence keen to have the moment captured. But what they did not know was that the Olympic flame itself would be travelling down the platform and flying more than 70 metres into the night sky.

“I had been shooting tons of not very good pictures on long lenses looking down into the cauldron,” Martin explained. “And then the flame started coming up and I thought, ‘Crikey, it is coming to us’.”

Fortunately, in his quest to make the very best of what he thought was a dud gig, Martin had been quietly manoeuvring himself down towards the start point for the jumper.

“I had talked my way down the ski jump, chatting to the security guards, showing them my cameras, just being friendly and they let me go in front of them,” Martin said. By the time the whole stadium, and indeed watching world, was looking up at him, or more accurately Norwegian ski jumper Stein Gruben, Martin found he was in the perfect position.

“After two hours I was 10 metres away, after three hours I was four metres away and by the time he jumped I was two metres away,” the photographer said. “I got that close in the last two minutes, thinking, ‘If I go now, they won’t kick me out’. So I jumped down two more steps at the last minute, took the picture and then got out of there before anyone realised I had got so close.”

The resulting picture not only purveys the gasp-inducing nature of the stunt, but also the magical nature of the night itself. Martin is most proud of recognising late-on just what was needed to ensure he captured both.

“For me, it is the fact you can see the whole stadium in the background and you think, ‘Crikey, that is a huge stadium and he is going to disappear into a tiny pin drop’,” Martin said, the awe still evident in his voice. “The beauty of it is the super wide lens angle I used. It helps to accentuate it all, so he looks even higher and it looks like even more like a cauldron. There is a little bit of optics helping you out. Sometimes sports photographers sit on a telephoto (lens) for ever and don’t take a step back and shoot on a wide angle but wide angles are great. You can get so much in and give the picture a real sense of place.”

The main protagonist in what has become one of the iconic Olympic Winter Games photographs ended up, much like Martin, unexpectedly central to proceedings. The 1988 ski jump team bronze medal winner Ole Gunnar Fidjestol had been due to take on the nerve-jangling task of carrying the most famous flame in sport until he injured his back just two days before the Ceremony. But, despite admitting to feeling “daunted just standing up there”, photographer Martin is adamant he was never worried about the fate of the Olympic fire.

“They can all do it, can’t they?” Martin laughed. “Norway has got loads of great ski jumpers.”

Upon what was indeed a successful landing, Gruben passed the flame on to the visually impaired cyclist and cross-country skier Cathrine Hazel Ingnes, before Norway’s Crown Prince Haakon Magnus lit the cauldron.

But Martin, who at the time was finally appreciating his spot as the “best seat in the house”, knew the Ceremony’s big moment had long since passed.

“As soon as I got that shot in the bag that was the job done for the day,” he said. “I knew I had got something special.”

Not only had Martin secured the signature photograph of the Games, he had also picked up a hugely valuable lesson. One he has spent a career heeding.

“You only learn when you are older that getting one great picture is what it’s about,” he said. “It is only by getting pictures like that and seeing what effect they have that you realise how important the big or the special picture is. Getting that picture was part of my journey to becoming a good photographer. All I want to do now is get a picture no one else has got.”