Nishi springs a last day surprise

With the majority of the equestrian athletes travelling long distances to reach Los Angeles, the logistics of transporting their precious equine cargo in a safe and humane manner presented an additional dilemma.

The Dutch, who faced the most arduous journey, travelling by ship via the Panama Canal, even went to the innovative lengths of building a treadmill to keep their horses fit during their passage to the Games.

Gratefully the full cohort –man and beast included – arrived in a secure and timely manner, with the Olympic Report stating that “the horses all stood the trip exceedingly well and their participation was not noticeably affected by their long journeys.”

Traditionally, many show jumpers had learnt their horse riding skills while serving as cavalry officers and 1932 was no different. One of the most distinguished riders to perform in the Los Angeles equestrian events was Takeichi Nishi, an orphaned son of a hereditary peer of the Empire of Japan. Despite inheriting his father’s fortune before he was 10, Baron Nishi harboured a strong desire to join the military and in 1916 entered Army Cadet School. Before long he had ridden his first horse and soon began honing his talents on horseback while climbing the military ladder.

In April 1922, Nishi was presented with an opportunity to fully focus on equestrian sport while continuing his military career when he was ordered to join the first regiment of the Japanese Cavalry.

By the end of the decade – now married with two children – he had risen up both the sport-ing and military ranks, promoted to first lieutenant and now a strong contender for the Japanese team that would compete in Los Angeles. He was even included in a convoy of visitors to the Olympic equestrian facilities, a trip that saw him meet a number of celebrities including film stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. What was intended as a reconnaissance mission turned out to be a social awakening, with Nishi enjoying nights out with his new, high-profile acquaintances, along with young officers from around the world.

In July 1930, during a visit to Italy, he purchased a new horse Uranus, and the following year was formally selected to represent Japan in Los Angeles. The team set up base in a rented house near the Riviera Country Club and Nishi again assumed the rule of playboy-in-chief, driving to training each day in a brand new Packard Convertible luxury automobile.

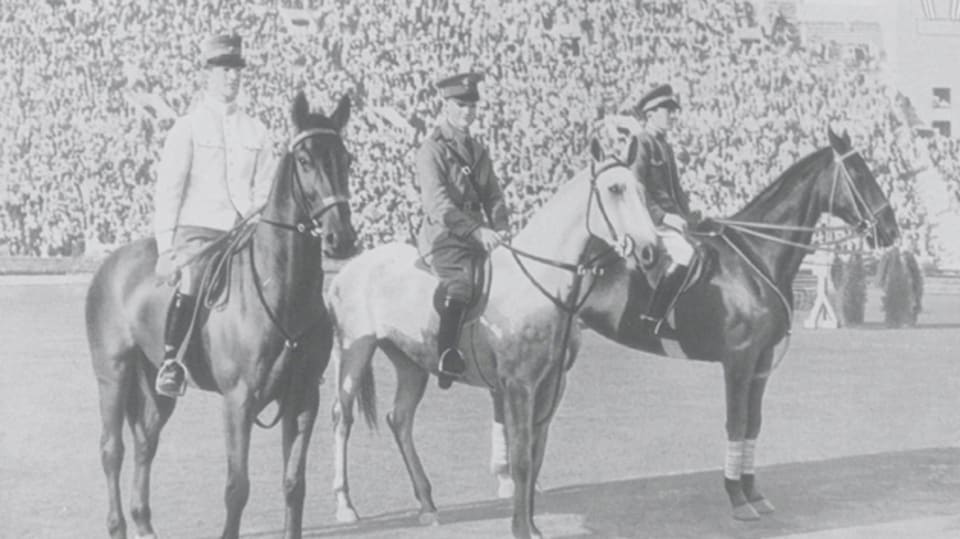

With the equestrian events not scheduled until the final day of the Games, there must have been some risk of Nishi burning himself out before he had even competed, but on 14 August, the 30-year-old showed the watching crowd of 100,000 packed into the Olympic Stadium that he knew how to work hard as well as play hard.

Competing against favoured opposition in the last of three equestrian events – the prestigious Prix des Nations jumping event featuring some eighteen obstacles of varying heights – Nishi completed the course in 2 minutes 42.2 seconds to win gold.

His victory was described in a Pennsylvania newspaper the following day as “one of the greatest surprises of the games”, with Nishi beating off the challenges of “the crack horsemen of the United States, Sweden and Mexico to capture individual honours.”

It was a fitting end to a memorable Games, whose closing moments were evocatively described in the same newspaper report as follows: “Then came the booming of canons, a fanfare of trumpets, the lowering of the Olympic banner and the extinguishing of the Olympic torch, signalling the finale of the greatest international sports contest in history.”

For Japan, Nishi’s gold medal was just one of several collected in Los Angeles against expectations, but none other captured the public imagination more than that won by the budding social mover and shaker. Indeed, following the Games, Nishi became something of a celebrity in his own right in America ad even received an honorary citizenship to the city of Los Angeles.

Nishi competed again with Uranus at the Berlin Olympic Games four years later, but neither he nor his compatriots were able to replicate their 1932 success.

Then came World War II and the various arenas of conflict that, in December 1941, saw Nichi’s nation of birth go to war against the country that had taken him to their hearts.

Nishi returned to the Japanese Army and in 1943 was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, where he was assigned as commanding officer of Iwo-Jima, an island 1,250km south of Tokyo.

He died in March 1945, soon after the United States Forces landed at Iwo-Jima, and while the nature of his fate has become the subject of folklore, perhaps the most poignant version claims that while defending the island he carried the whip he had used during his Olympic victory, along with a lock of Uranus’ mane in his breast pocket.

Furthermore, equally heart-rending is the supposed destiny of Uranus, who is said to have succumbed to illness just seven days after Nishi’s own demise.

To this day Nishi remains the only Japanese Olympian to win an equestrian gold in the history of the Games.